This post means to wrap up a journey that started long before my studies in Sustainable Development; and one that will continue to become long after.

It has been almost a month since I officially got that final ‘pass’ on my master thesis. The belated graduation date had nothing to do with my planning habits. During the last miles I encountered some obstacles, many of which I had somewhat anticipated. These obstacles were shaped by my lack of scholarly experience, but also by my research subject—ecocentric worldviews—being a soft and fluffy one, and my examinator having a hard science background. “Yes, putting my bare feet in the dirt and chanting words under a February full moon formed essential parts of my research experience.” I had to remind myself that soft does not mean weak. Exploring philosopical and value-driven roots of cultural habits is essential if we want to truly right our wrongs. Encouragement and praise from both my supervisor and subject reviewer helped me stand my ground. “Yes, my research does indeed work with the broad but proven assumption that alienation from nature in Western cultures explains unsustainable behaviour.”

Once I have finalised editing my own (artsy, esthetically pleasing) version of my thesis I mean to publish it on this platform for anyone who is interested. I have spent too many hours spitting through critiques and evidence on the human-versus-nature rift that exists in Western societies for me to dedicate any more time to problems. Instead, I will take a leap and share with you the main ecocentric lessons that personal conversations with ecocentric practitioners and personally engaging with their work have taught me. They are directly copied from the concluding chapter of my thesis called ‘From Anthropocentrism to Ecocentrism — Lessons from ecocentric practices in eco-art and ecotherapy’.

Ecocentric lessons

Together, six identified ecocentric themes allow for a deeply personal understanding of ecocentrism that is reached through practice and embodiment. In comparison to the principles of deep ecology (Naess & Sessions, 1986), ecopsychology (Roszak, 1992) and Land & Earth Ethics (Leopold, 1989 [1949]; Callicott, 2014), these value-driven themes are relatively open-ended and do not mean to dictate specific actions and beliefs. Instead, they advocate for an understanding that transcends an intellectual definition, and may come to have varying interpretations and expressions for different people. Still, when imagining others to engage in similarly immersive activities and deeply connect with nature, I do not think it far-fetched to assume that notions like intrinsic value and codependency are embedded in all these themes.

The first concrete lesson is more of a remembering of the human species being nature: we are born as nature and will one day return to be part of Earth’s cycles, however we spend our lives and regardless of if we forget our interrelatedness with nature. This is an essential aspect, as there is a clear perceived and practised divide between humans and nature, which allows and enables harmful, unsustainable behaviour. Engaging in nature-oriented activities can benefit physical, emotional and mental well-being and even increase social cohesion. In remembering that we ourselves are nature, we may notice similarities existing in the flows, communications and connectivities that exist outside of ourselves to also exist within us. We may come to feel an enhanced sense of belonging and kinship with the more-than-human world.

Pluriversality allows for multiple truths and beliefs to co-exist alongside each other. As colonisation and the domination of a singular worldview are identified to cause unsustainable practices and relations, the ecocentric lessons as uncovered in this thesis allow for a pluriversal existence in which not one view is deemed as superior. Ideologically speaking, if the entire world was to reach an understanding of all six themes, it would be unthinkable for one person or culture to feel justified in imposing their worldview and moral compass onto others. If people deeply believe that their own worldview is valid, and that others hold similarly valid worldviews that may differ, this automatically de-validates monistic notions.

Connection can be found in a multitude of ways, which can alleviate a sense of isolation, and increase a feeling of being held by our home planet. In establishing relations with external and internal environments as well as multispecies communities, we can develop enhanced awareness of cycles, changes and transformations that occur. For example in changing seasons and climate, but also in our emotions and other internal processes. Ecocentric practices awaken our senses and other innate abilities—like intuition and kinetic awareness—that all allow us to look and perceive better. As Blanc Sceol says: “You see through your body”.

In recognising that life on Earth is never static, but always changing, transforming, and becoming, this makes linear notions of growth and development simplistic and limiting. Noticing how transformation occurs, we can honour change and take lessons out of potentially difficult situations. This is essentially realising that humans, despite having a major impact on Earth’s systems, do not exist in a vacuum and are not as much in control as ideological colonial thought is based on.

Instead of fixating on collaboration and beneficial symbiosis, which of course are important, the ecocentric theme of co-creation honours how we shape the world through simply partaking in it. It is impossible and unrealistic for our entire more-than-human world to live in harmonious and nurturing relationships. Paired with autonomy, this ecocentric lesson opens up possibilities to take on a more active role in not only our own well-being, but also that of the planet through non-linear reciprocal relationships. Additionally, accepting that strong inclusions lead to strong exclusions (and vice versa) allows a working around that without getting stuck on having everyone and everything on board with one’s beliefs and visions.

And, finally, an ecocentric value that lies at the foundation of my thesis is that life is a subjectively felt and deeply personal experience. Whereas science—paired with our intellect and rational thought—is essential in understanding our human and planetary systems, the appreciation of how our deeply personal perceptions and experiences are always present carries the potential to deepen and enrich our lives in any area. This also values other ways of knowing that transcend the mind and involve entire bodily systems.

Stripped down

With the scholarly part of my research behind me, I can now focus on my own more emotional and embodied understanding of what I have learned. I feel a need to shed terms like ‘ecotherapy’ and ‘ecocentrism’ that have become second nature. I already have a primary nature. One that requires no prefix and I will use to share my ‘eco’ and generally nature-oriented normal. This normal has me walking barefoot on muddy tracks, playing in the river on a rainy day, and napping on sunwarmed rocks.

I have found a home on Earth, which isn’t as self-evident as that sounds. Everyone deserves to have a sense of belonging on this planet. This belief drives me to keep sharing my views, as well as art and nature-based practices, with others. And although I currently find myself in that liminal gap between graduation ceremonies and more practical matters like job applications, I will not let any fear of the unknown or insecurities take hold of me. On a bad day I will simply lay on my back and stare upwards. As long as I can hear the birds sing, I am not alone. As long as I can see the sky, I am free. As long as I can see the sun rise and set, I know love. And heartbreak. As long as I can feel the wind, rain and sun on my skin, I am alive. As long as the Earth beneath my body holds me as though I belong here, I have a home.

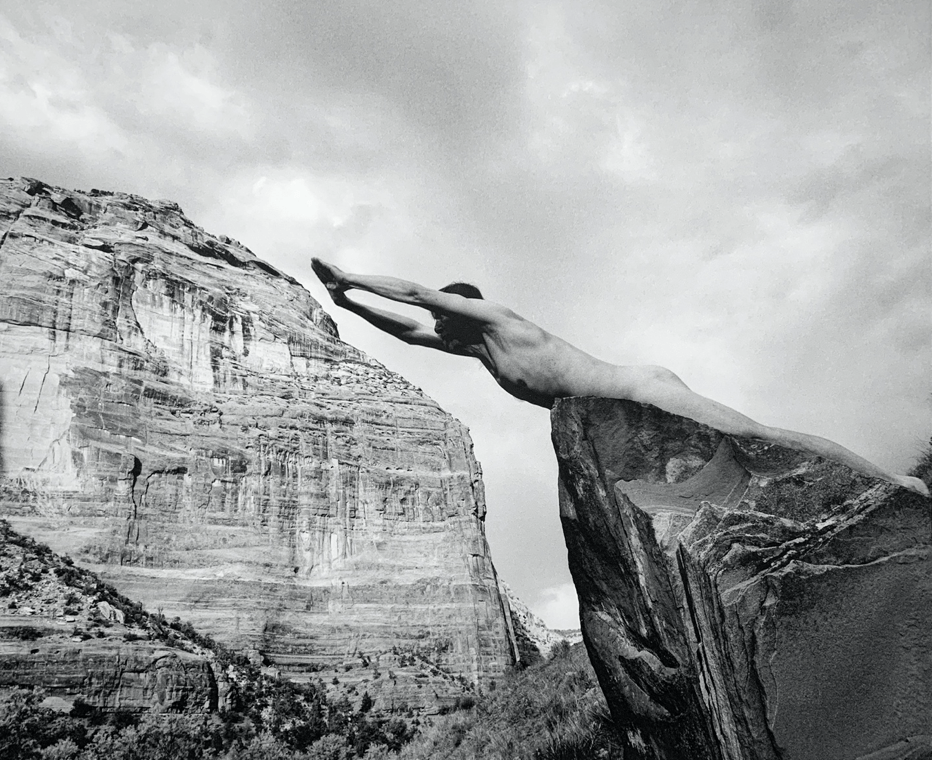

To finish off this chapter, here is a quote from an essay that Arno Rafael Minkkinen wrote in his 2008 book titled Homework: The Finnish Photographs of Arno Rafael Minkkinen: 1973 to 2008:

“My first photographs in Finland, taken in 1973 in Nauvo, confirmed for me the sanctity of human nudity. The essential bareness that surrounds everything in nature surrounds us as well. In Finland, where nature can be at its most glorious, to be nude and alone in the forest or on some shoreline vista may be the closest one will ever get to the experience of creation. I love digging my toes into the forest floor or navigating the boulders along the lake shores barefoot and bare ass like a monkey in heaven.”

May we all remember that we are nature, not above or below it. May we all remember to strip down and play outside like bare ass monkeys in heaven (the one on Earth).

Reference(s)

Callicott, J. B. (2014). ‘Thinking Like a Planet: The Land Ethic and the Earth Ethic’. New York, 2014; online edn, Oxford Academic, 23 Jan. 2014. [https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199324880.001.0001]

Leopold, A. (1989). ‘The Land Ethic’. A Sand County Almanac, pp. 201 – 227. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press Commemorative Edition, 1989 [1949].

Naess, A., Sessions, G. (1986). ‘The Basic Principles of Deep Ecology’. The Trumpeter, 3(4). [https://trumpeter.athabascau.ca/index.php/trumpet/article/view/579]

Roszak, T. (1992). ‘The Voice of the Earth’. First Touchstone Edition, Simon & Schuster, 1993.

More Chapters

-

Chapter 2: Fractured

In this post we dive into what it means to have a fragmented perception of ourselves and our surroundings, and trace the cracks to find out how deep these might… read more ꩜

-

Chapter 1: How on Earth did we get here?

An introduction to a new (or rather ancient) perspective on planetary health, and embarking on a joint journey of discovery. We find ourselves on a planet that has many secrets… read more ꩜

Leave a comment